Walking Algorithms¶

The way in which an animal or a robot walk is called a gait – it tells us how and in what order the legs are moved, how the body is balanced and how it moves forward.

Statically and Dynamically Stable Gaits¶

When the robot walks, it has to keep its balance. There are two general strategies for doing that, and according to them, we divide the gaits into statically stable and dynamically stable.

For statically stable gaits it doesn’t matter how fast they are performed, or whether the robot is stopped in a middle of a step – it is stable at any moment, at all times. Animals and people use those gaits when they want to go slowly, or when they want to be able to stop at any time. An example of such a gait is the “creep” gait, used by cats stalking their prey.

Dynamically stable gaits are much harder, as they have to be performed at a particular speed and cannot be interrupted at an arbitrary point. They are sometimes called “controlled falling”, as they exploit the fact that it takes some time for the robot to fall when it’s unstable, and that time can be used to move the legs in such a way as to prevent the fall. Most animal gaits are dynamically stable, as they tend to be faster and more energy-efficient. An example of a simple dynamically stable gait is the “trot” gait.

Area of Support¶

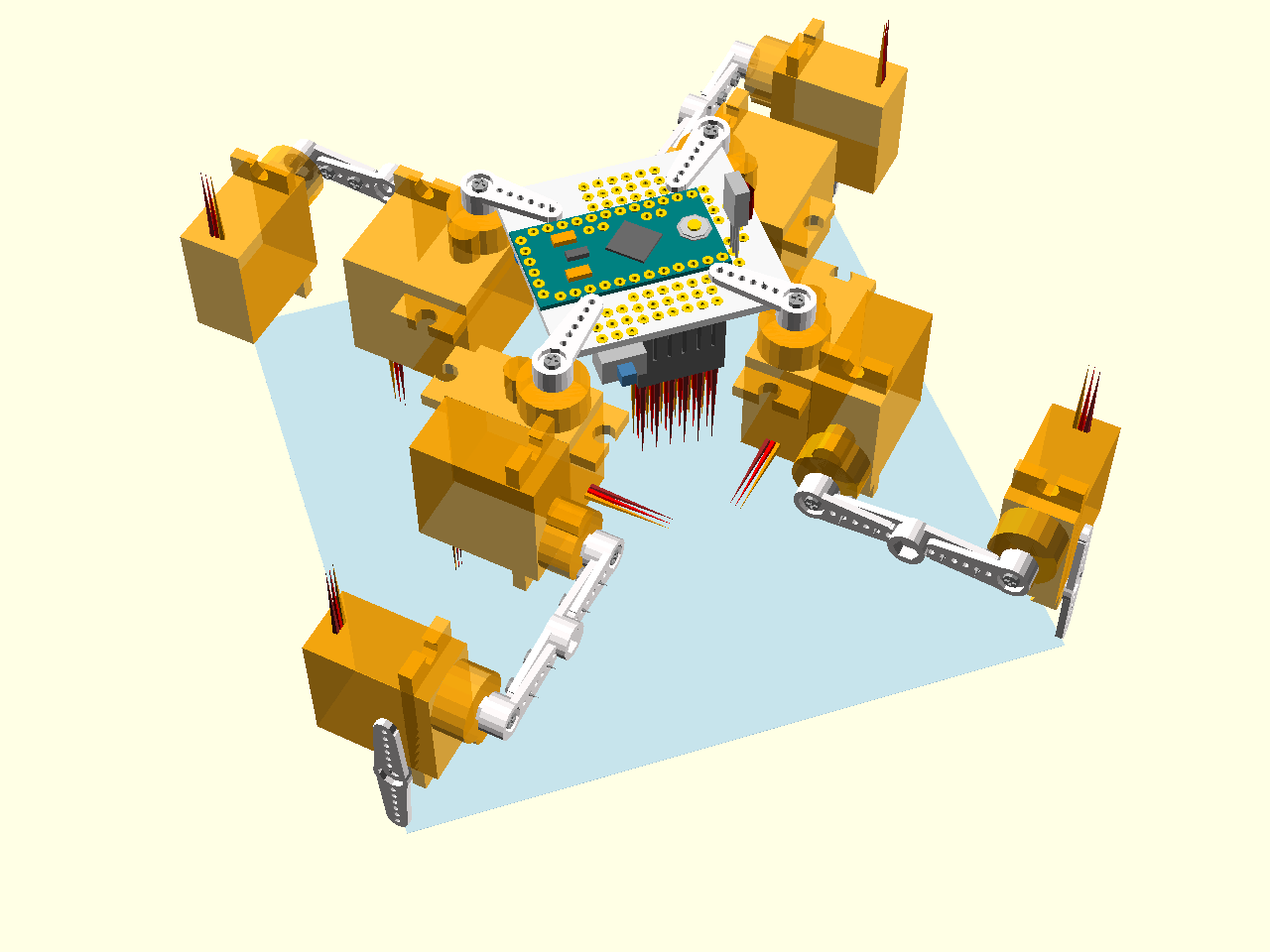

I order for a relatively light robot, like ours, to be statically stable, it has to keep its center of mass somewhere between its legs. More precisely, if you connect all the feet on the ground with straight lines, so that they form a convex polygon, the center of mass has to be located directly over it. We call that polygon the “area of support” of the robot at the given moment. The area of support will change depending on which legs are placed on the ground and where, so the robot will sometimes need to shift its center of mass around to remain stable while changing its stance.

The image above shows the are of support of our robot in the starting position.

In a heavier robot, you also have to take into account the inertia, so that it’s not sufficient to just track the center of mass – you have to track the so-called “zero-moment point”, often abbreviated ZMP, which is basically the point on the ground directly below the center of mass, shifted to account for the inertia. We will not get into details of that here, as our robot is light enough that just leaving some small margin around the area of support is enough.

Raising a Leg¶

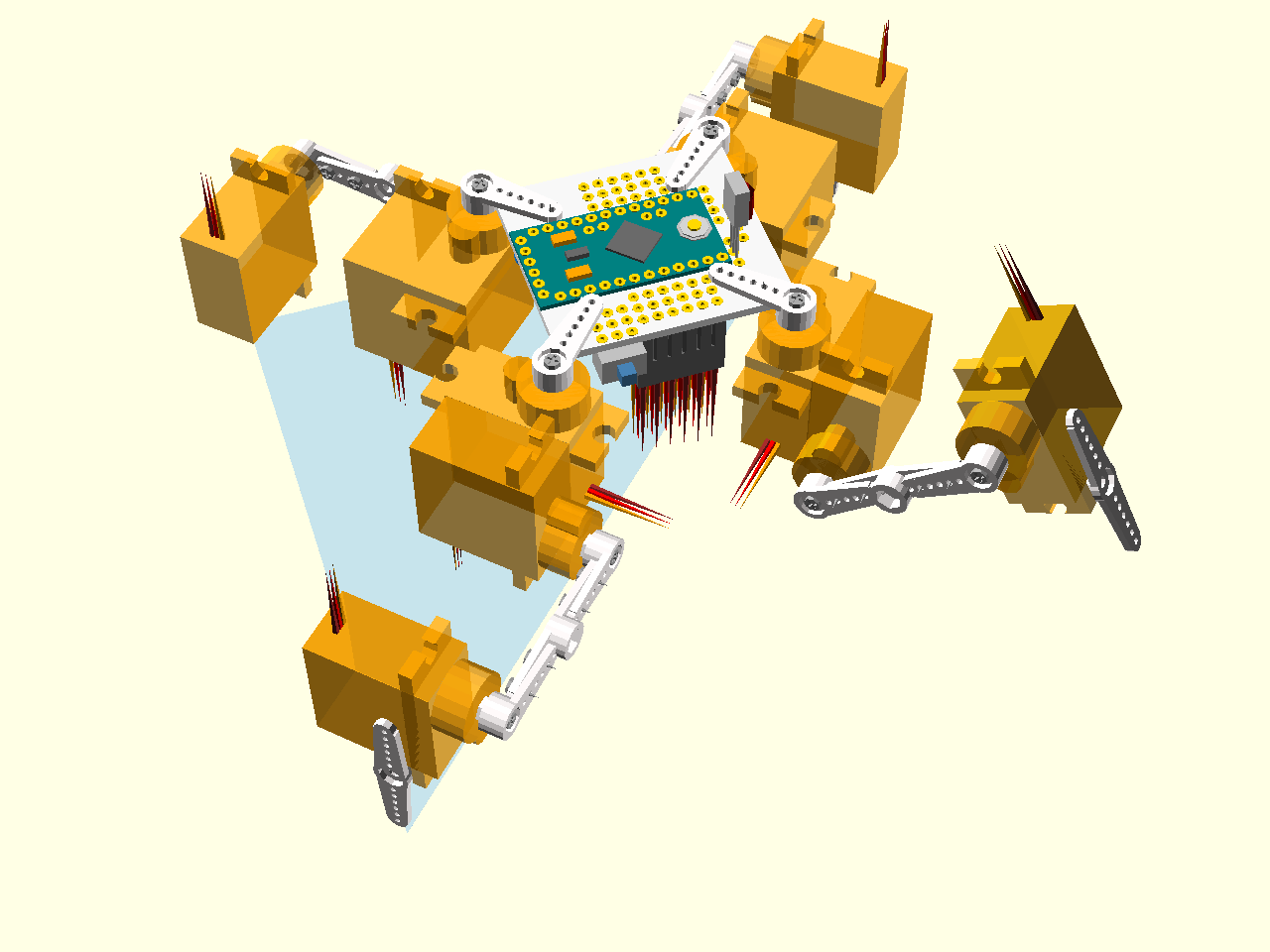

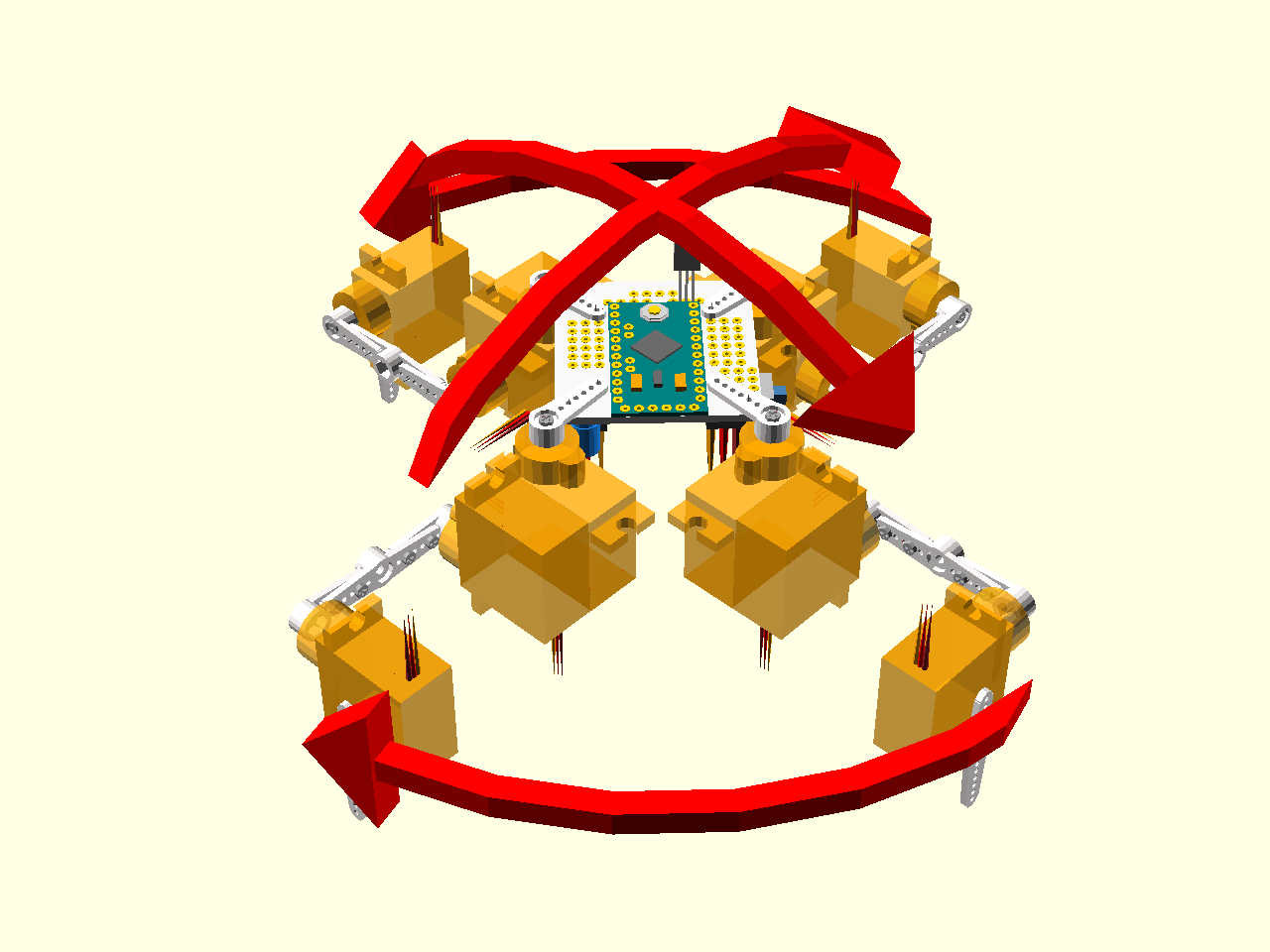

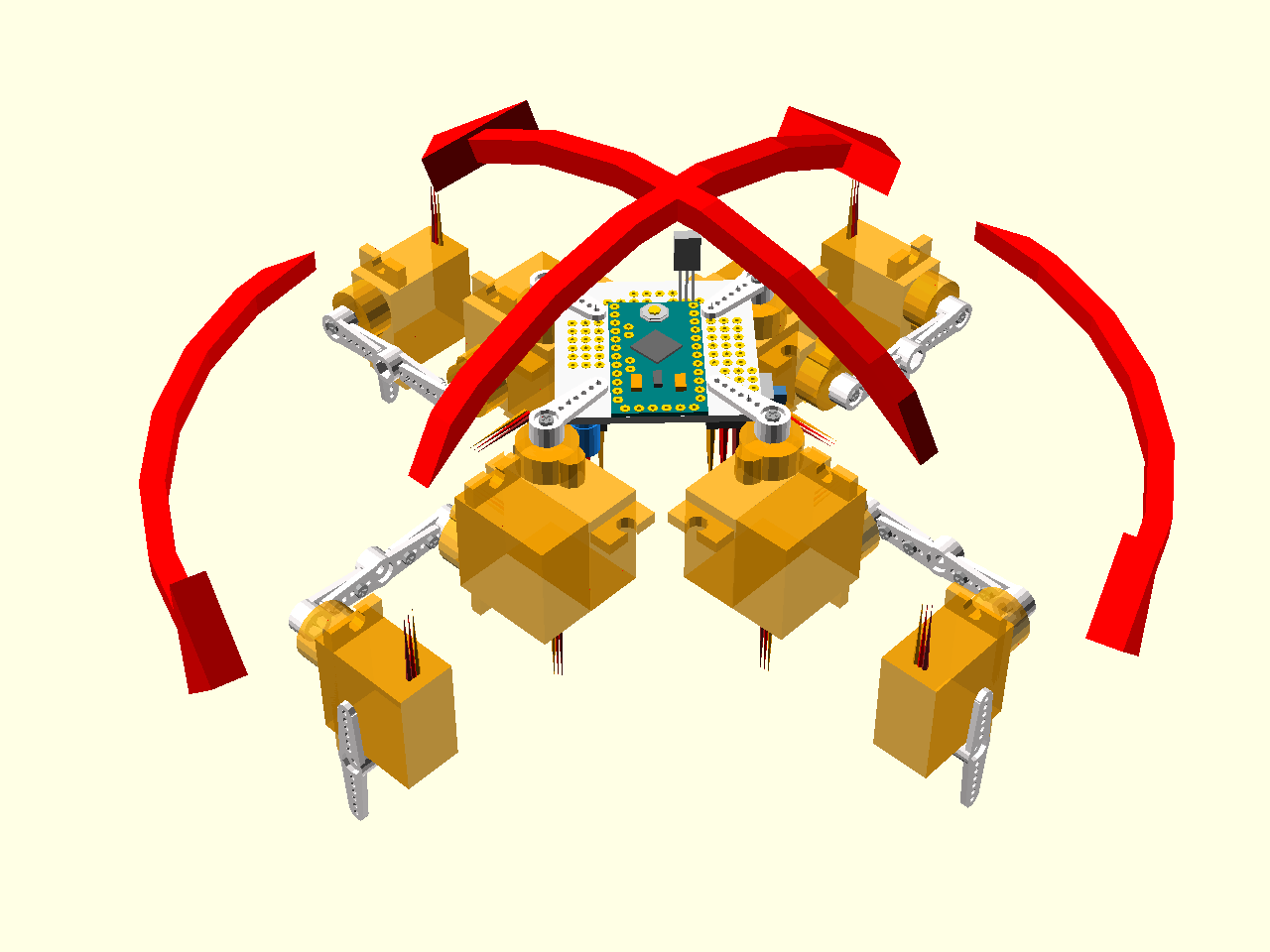

When the robot raises one of the legs, its area of support changes dramatically:

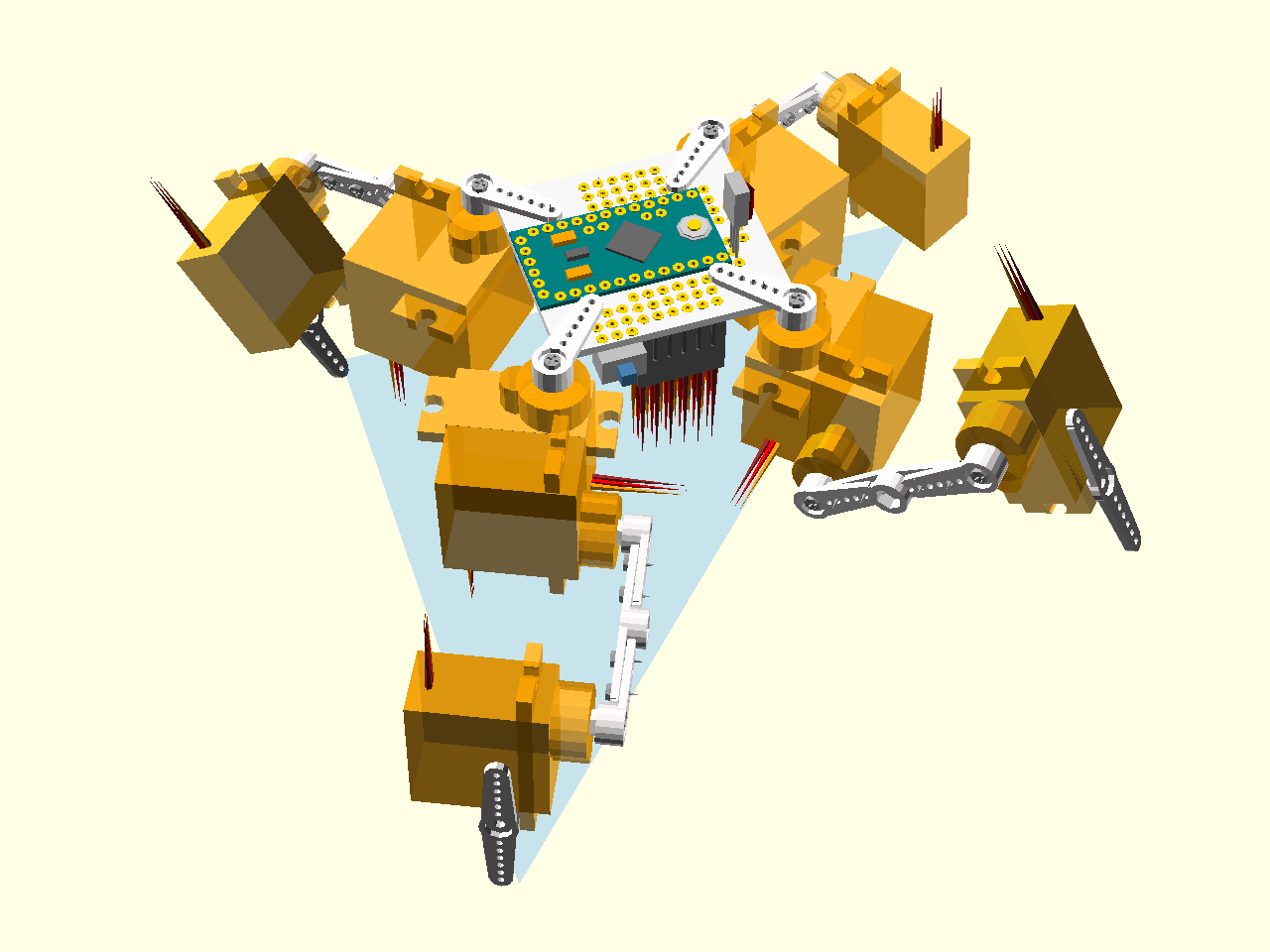

You can see, that our center of mass is directly on an edge of our area of support. That’s bad, because the smallest force can now tip our robot and make it fall. We can avoid that by moving all the legs toward the one leg that we want to raise before raising it, so that the center of mass shifts:

There are also other methods of balancing, not covered here. For example, many animals have a flexible spine, that they can bend sideways to shift their center of mass. Other animals have tails that they use to balance. Possibilities are endless.

Moving Forward¶

Our goal is to propel our robot horizontally across the floor. The simplest solution to do that, at least initially, is to just move all the legs that are touching the ground backwards. If we do it slow enough, so that they don’t slip, they will stay where they were, but move the body of the robot forward. This is an excellent way of moving around, and many industrial robots do it this way, bolted to the floor in one place. There is however a small problem: the range is quite limited. Sooner or later you will either move your center of mass outside the support area, or your legs move to their maximum range. What then?

Then you raise the legs from the ground, move them forward, and set them down in the new place. But you have to be smart about it, because if you do it with all the legs at once, you will fall down. But you can raise a single leg and still stand on the remaining three. You can also raise and move that leg while moving the remaining legs backwards, which saves you some time and makes it both faster and more smooth.

Now, as you know, if you are raising a leg, you also have to make sure that the center of mass stays inside the support area. To do that, you will have to shift the robot’s body away from the leg that you are rising. Since you are shifting your body forwards, it is also important in which order you raise the legs – some orders will be more stable than others.

- So, to sum, our plan of action is:

- move all the legs that are on the ground backwards,

- for each leg in a set order:

- shift the body away from that leg

- raise the leg

- move the leg forward

- set the leg on the ground.

The Creep Gait¶

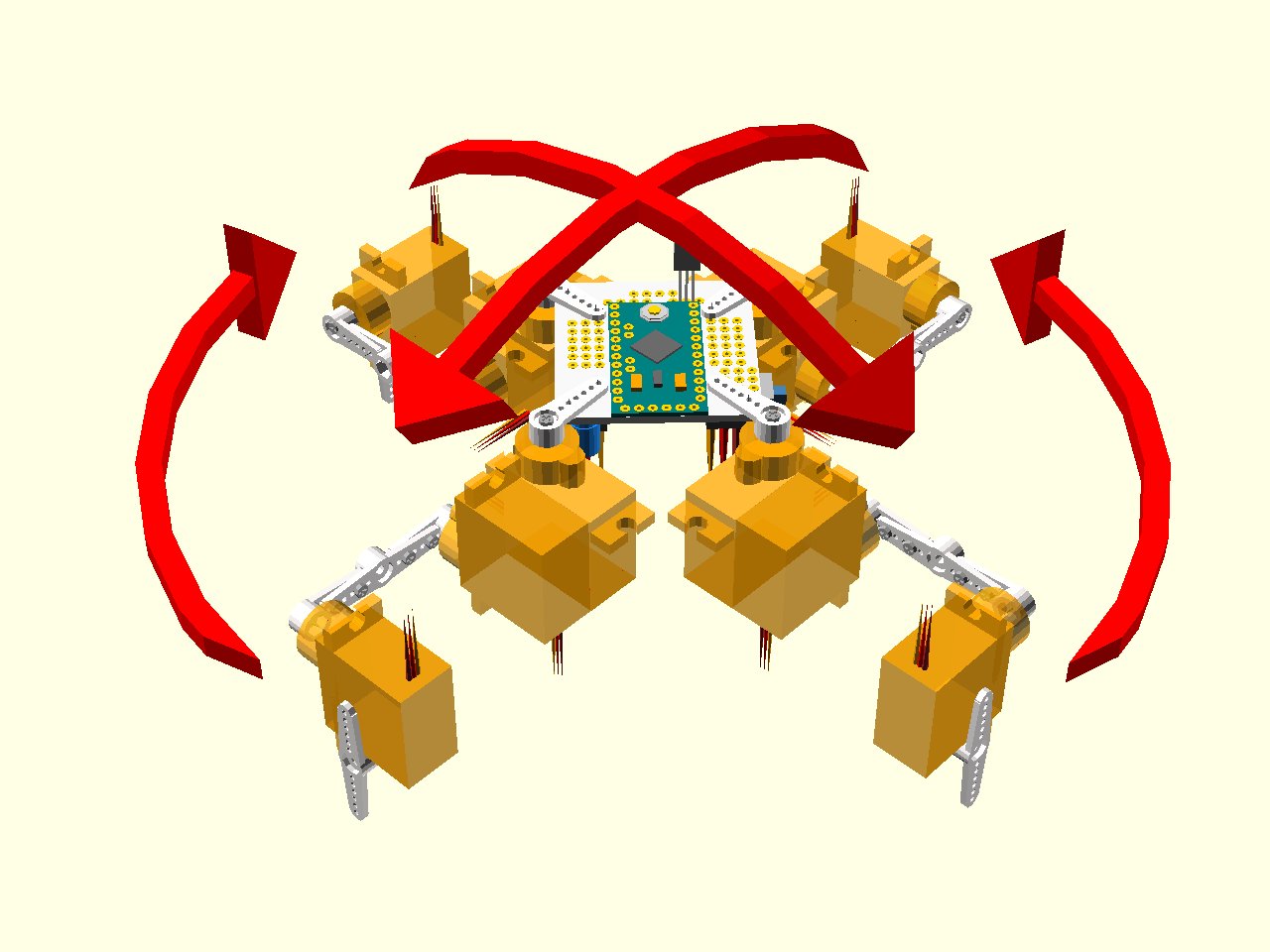

What order is the best for making steps, if you raise one leg at a time? There are four possible orders, assuming you always start with the same leg, and ignore the orders that are just reflections.

Both calculations and experimental data show that the last one, a figure eight orthogonal to the direction of walking, provides the optimal stability at all moments. Note that this order is best only when you are moving forward. If you are moving sideways, backwards or rotating, then other leg orders are optimal. That’s why it probably makes sense to adapt the order to the situation.

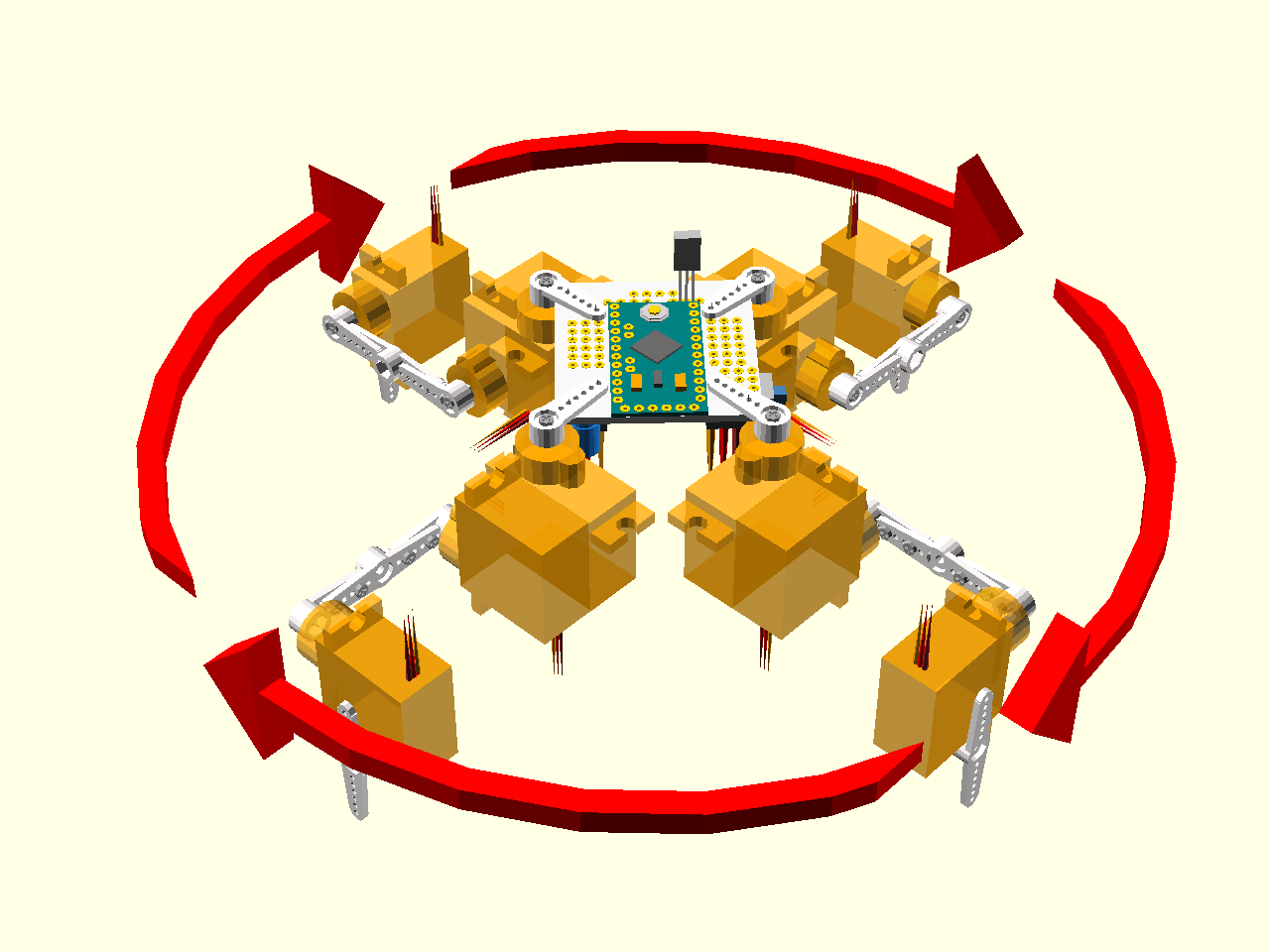

The Trot Gait¶

The creep gait is stable, but quite slow – raising only one leg at a time, you can’t move the remaining legs backwards too fast, or you move out of the range of your legs. In addition, shifting the robot’s body before each step also takes some time. Is there a faster way?

Turns out that you can move two opposite legs at the same time, if only you do it fast enough, so that the robot will not have time to tip on the two remaining legs. This is not a statically stable gait – you can only stop safely between steps, when all the legs are on the ground, but it’s more than twice as fast as the creep gait: first, you move two legs at a time, and second, you don’t have to shift your body for balance.